When it comes to writing these lines, we continue with the excitement left by the Bertsolaris Main Championship Finals in Nafarroa Arena. For three months, 42 bertsolaris have demonstrated their ability to create art at once and the Basque media have followed up orderly. Those of us working on Wikipedia have also tried to keep track of the day by day, sort it by points, define the big zortzikos and small tenths and improve the bertsolaris articles. We have also tried to write history, go through the First War of Verses of 1935 and write about the championships organized by Euskaltzaindia in full Franco. We have tried, but the exercise has some gaps, the copyright. You can"t hear the voice of the bertsolaris on Wikipedia in Basque, or get a quality picture of the bertsolaris, unless a wikilari moves with a good test chamber. Without a free photo, you can"t illustrate it. Without a free image, knowledge is lost.

Since 2009 we have obtained a photo of each Bertsolari Txapelketa Nagusia from the hand of local media that often publish with free licenses. Flickr freely raised the numerous 2009 photographs from the public media from Larrabetzu to the digital platform; UKBerri did the same in 2013; Dani Blanco, from Argia, uploaded the photos from the end in 2017, and thanks to it we have the ones from 2022. The first two are local media outlets that have disappeared: if they had not freely uploaded their file to Flickr, they would be lost forever. If we hadn"t copied these files on Wikimedia Commons, it would have been impossible for it to have been a photo of late 2009. As of 2009 the situation is worse, we are immersed in cultural events without a free image. We have a few 1967 photos that the Marin Fund went up to Kutxateka and that the Gipuzkoa Foral Council left free. There are Xalbador, Garmendia or Mugartegi, a bertsolari that we only know from behind. Further back, a 1936 photograph, uploaded by the Car Fund, the men with their champion in serious training. Meanwhile, darkness.

Wikipedians, like thousands of people who are betting on free knowledge, generate content for recreation. It"s an option, it"s not mandatory. Wikipedians in Basque do so in Basque and we try to multiply the forces of free content in the Basque community. In recent years we have developed various projects in order to release and reuse media funds. The four projects carried out with Tokikom and Berria stand out. I want to talk about them.

Tokikom's media are published under the license CC-BY-SA , compatible with Wikipedia. This allows images to be reused whenever the identity of the author is recognized. This license has allowed us to digitize the historical photographs of four media (first step if we want images from the 1990s), upload them to the Wikimedia Commons cell, of which hundreds of articles are already being used.

The first attempt was made with Aiurri, quite experimentally. 2,100 photos were uploaded (available at https://commons.wikimedia). org/wiki/Category:Images_from _Aiurri), carried out between 1990 and 1997. The construction works of the A-15 are already present, some of the few free images of the insumission movement, B.A.P!!! A presentation by the group has already disappeared in the gaztetxe of Andoain or the free photos of Martin Ugalde, a man we haven"t known before.

We continue with the Ttipi-Tapa with the lessons of the Aiurri experience. 2,020 photos were uploaded (available at https://commons.wikimedia). org/wiki/Category:Images_xliff-newline _Ttipi-Ttapa), including the only free photograph of the Itoiz group, that of several pelotaris and politicians or that moment was sung by the mountaineer Félix Iñurrategi at the Bertsolaris Championship of Navarra of Navarra. Then came Baleike and Guaixe. And we"ve also uploaded hundreds of Korrika photos to Commons that went up to Aiaraldea to Flickr. Uztarria has also yielded hundreds of photographs of the Basque Theatre Meetings in Azpeitia that allow us to fill a particularly difficult gap. In short, taking pictures on the street is possible, but in the performing arts it is practically impossible. The media play an important role in this area.

We continue with the Ttipi-Tapa with the lessons of the Aiurri experience. 2,020 photos were uploaded (available at https://commons.wikimedia). org/wiki/Category:Images_xliff-newline _Ttipi-Ttapa), including the only free photograph of the Itoiz group, that of several pelotaris and politicians or that moment was sung by the mountaineer Félix Iñurrategi at the Bertsolaris Championship of Navarra of Navarra. Then came Baleike and Guaixe. And we"ve also uploaded hundreds of Korrika photos to Commons that went up to Aiaraldea to Flickr. Uztarria has also yielded hundreds of photographs of the Basque Theatre Meetings in Azpeitia that allow us to fill a particularly difficult gap. In short, taking pictures on the street is possible, but in the performing arts it is practically impossible. The media play an important role in this area.

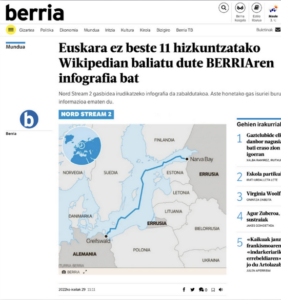

It is clear, and there should be evidence, that the most significant photographs of Basque culture are taken by the Basque media. Nothing weird seems to me. But what happens when the news turns around the world? What happens, for example, when a state that has not yet been fully resolved breaks a Nord Stream pipe transporting gas from Russia to Europe? For a few days, in all the languages that had an article on Wikipedia, the map of Berria in Euskera was displayed, as well as in English Wikipedia, which has the most visits worldwide.

A few years ago Berria modified its license and established the Creative Commons–Attribution-ShareAlike license (cc-by-sa-3.0). The change of licence affects all the texts produced by Berria, the images and videos produced by them, but not the material produced by other agencies. This has allowed us to use different texts on Wikipedia, either to report a death or to complete a text of a scientific topic. We often use texts produced by Elhuyar to feed this scientific objective. Texts are rarely interchangeable because the style of Wikipedia is not journalistic. But there are complements.

The result of this license change was the upload to Wikimedia Commons of thousands of infographics by Berria. These infographics include graphics related to the socio-economic situation, mountain routes or infographics on the Chernobyl disaster that were very successful. With these images we have been completing a series of articles whose result is spectacular: since we started to upload the infographics, the articles containing them have had more than 25 million visits. Yes, you"ve read well, over twenty-five million. It is true that about 10 million of these visits took place in a single month, in which the Chernobyl tv series was very successful. But each month they receive over 250,000 visits, of which about 15,000 are in Basque. That is, they read mostly infographics in Basque throughout the world.

Yes, free content and cultures are beneficial. They are beneficial in the short term because they help shape an ecosystem, because in a language as small as the Basque language we do not have enough resources and multiplying the content helps to create new references. It is beneficial because in the short term we can release discoveries such as the hand of Irulegi, both in a local media and in Wikipedia, recognizing the authors and disseminating the contents worldwide. Because the only way that can help us create our conversation issues in the short term is to have the ability to freely disseminate content. We see that the agenda is outside, but it doesn"t have to be that way.

Yes, free content and cultures are beneficial. They are beneficial in the short term because they help shape an ecosystem, because in a language as small as the Basque language we do not have enough resources and multiplying the content helps to create new references. It is beneficial because in the short term we can release discoveries such as the hand of Irulegi, both in a local media and in Wikipedia, recognizing the authors and disseminating the contents worldwide. Because the only way that can help us create our conversation issues in the short term is to have the ability to freely disseminate content. We see that the agenda is outside, but it doesn"t have to be that way.

Free content and cultures are beneficial in the medium term, because we create a new culture, not today — focused on it — over those everyday creations of care and cultural cooperation. It is a culture that will help us to make better use of resources, to build bridges between our media, to ensure that we always — in any case — have something at our disposal. It allows us to broaden our daily scrubs and understand the forest as a whole. Besides generating references, they facilitate the documentary work.

Finally, free content and cultures are beneficial in the long term, as they help us to better understand the culture, history and society of Euskal Herria. The Verso War of 1936, with a single image, better illustrated than other passages that have been much closer to history. Because as we deliver content to Twitter, Facebook and Google, we improve the content that will be outside this digital feudalism. Because we create digital files, through prosperity, multiplication, redundancy. Wikilarians often find dead websites. They have disappeared. They attend. We"ve lost them forever. The creation of free files allows us to get rid of this forgetfulness, legally and usefully keeping the most important content. Because we face the so-called Digital Middle Ages.

I did not want this text to have a clear manifesto tone. At least it was not my intention. The Basque media community is small, perhaps less than necessary. But in its smallness, it has managed to reinvent itself over and over again, to reach new places, to address challenges that big languages do not face. We have internalized the idea that if we don"t do things, nobody will. The resulting free content ecosystem is a mere privilege. Wikipedians go out into the world often and it"s common to talk to encyclopedists from other languages. They wonder how many images can be obtained. We explained to them that it is common in the Basque press that the cc-by-sa licence is used and we are convinced of it. No, it"s not common. There are few communities in the world that allow us to do what we get in Basque. I think it"s a pride. Moreover, the spread of free culture is a mark of the Basque community. It is an anomaly in the general scope of the communication channels, a poorly sold anomaly. I will not propose as a motto “we are abnormal, abnormal in the world”, because it can be misunderstood. But I would like to propose that the idea be used. Let"s talk about our anomaly, let"s be proud, and let"s explain that if small languages want to create an ecosystem, it takes neighborhood work and sharing if they want to survive. This is at the heart of the Basque brand debate, because right now we talk so much about this concept. Euskera is attractive because it offers more possibilities to share content, because the Basque community is willing to grow together, prefers free content. The Basque media are sexy because they allow us to read and reuse their files, because few will allow us. I think we have an attractive containment symbol there, right?