«Although some legislative steps have been taken, the situation of women engaged in agriculture and livestock farming remains little known. In fact, the media discourse is built especially around the urban core».

1. Introduction

The members of the research group Visibility of Women in the Media have been analyzing the presence of women in the Basque media since 2016, and in this sense we have published several reports and articles in which it is observed that, despite the increased presence of women in recent years, there is still a long way to go. In this article, together with researchers from other European universities, through an analysis framed in a large study on rurality, the aim was to analyze the visibility of rural or rural women, analyzing their presence in the Sustraia program, offered by Basque public television EITB.

Hidden in the household chores, the work of rural women has been invisible, located in the private sphere and considered unproductive, although they are essential for the care of the vegetable garden and livestock. Without minimum rights adapted to workers, women's work has on many occasions entered into free needs in affective relations, and recently has been recognized for its legal contribution in the productive sphere, thanks to the fight carried out by women and feminist alliances.

Although some legislative steps have been taken, the situation of women engaged in agriculture and livestock farming remains little known. In fact, the media discourse is built especially around the urban core. The presence of the rural environment, on the contrary, is scarce and manifests from a point of view that we can consider romantic or related to the idea of emptying that occurs frequently, and that is accentuated in the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, if the world of agriculture is outside the media discourse, and considering that the presence of women in the media in general is far from parity, in this study we wanted to investigate the visibility of rural Basque women. To this end, in the television program Sustraia offered by the public body EITB on the primary sector, we investigated the presence and voice of women, taking into account that the collaboration agreement signed between the Basque Administration, the Foral Deputies of Araba, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa and EITB Media, S.A.U. in point 2, it states:

«Euskal Irrati Telebista - Radio Televisión Vasca, with the objective of contributing to equality between men and women, opens the gender perspective to the “SUSTRAIA” program, recognizing the work of women in a rural environment with specific barriers to the exercise of their rights and making their contribution to the innovative role of women in maintaining rural areas and in the transformation to a more sustainable model»

2. Theoretical Corpus

2.1. Women in the Basque rural environment

The Basque Government publishes every four years a report on women living in the Basque rural environment, the latest in 2020 in a situation of COVID-19 pandemic and therefore under specific conditions. However, we can draw some general data from this: although 73% of CAPV municipalities are rural municipalities (74% of the area), only 14% of the population lives in them, of which 49% are women. As stated in the report, the rural environment is no older than the urban environment, only 22% of women are over 65 and 26% of women in the urban environment (6). or ). Another significant fact is that the percentage of migrants is 9%, 2 points below the urban center. As for language, 42% of the population is defined as Euskaldun and 18% are bilingual. The report points out that the rural environment is still more Basque than the urban environment. Regarding the level of education, according to age, most of the women without education or with primary education (more than 80%) are those with the most advanced age ratio: over 65 years. On the other hand, at least 91% of rural women under 44 years of age have undergone professional studies and almost half undergraduate studies.

According to the report, rural women spend more than 30% of their daily time (almost 8 hours) on work (domestic, care or payment), and it has increased by 2 hours since 2016, 2 hours a day more than men. Time spent in care and paid work has increased and time spent in domestic work has decreased slightly. Rural women spend less time on physiological needs (eating, sleeping...) and work in general than those of CAPV. On the other hand, surveillance is invested almost three times more in rural areas and leisure is also somewhat greater. In addition, travel time is lower than the CAPV average. Since 2016, the time spent by women on paid work has been increasing, while by men it has decreased. Differences in the time devoted to domestic work remain, always to the detriment of women.

On the other hand, rural women dedicate 6% of the time (1 hour and 42 minutes) to caring for other people, while CAPV women dedicate, as a whole, only 30 minutes daily and 12 minutes daily to CAPV men. There is, therefore, a clear difference between the time spent by rural women on these jobs and the average of women in the CAPV. One of the explanatory factors would be the composition of the farmhouse, where several generations live.

As stated in this government diagnosis, the service sector is the one that concentrates most work activity, both among men and women, both in rural areas and in the urban environment. Over 86 per cent of rural women work in the service sector and 12 per cent in industry. Finally, in the primary sector, 1% of women are concentrated (in men it rises to 4%, according to this 2020 data).

Another point that is highlighted in the 2020 report is that almost 33% of rural women are involved in environmental activities. In addition, the higher the level of education and monthly income, the greater the involvement.

2.2. Invisible

Leire Milikuak on Earth, in the shadow. According to the book Women farmers and participation (2022), the work of women in the household has often been hidden or not considered as productive work, as in the case of men. Until recently there were very few women discharged from the Social Security Service in the agricultural sector and, in many cases, the work done in the farm has been considered as domestic work and not as exploitation. On the other hand, although formally the number of women owners has increased, this has happened many times on paper, but not really… This is closely related to the lower participation of women, because historically women have also performed care tasks and because the supply of services in the rural environment is smaller than in the urban center.

According to Amelia Jauregi of EBEL:

«As women, workers and peasants realized that there were “great problems and deficiencies in each valley”. At that time, women did not pay social security contributions and therefore “were not considered workers”. Most peasant women married in her husband’s house, “normally the one who left out had less authority, even more if she was a woman”» (Goiberri, 2016).

2.3. Alliances of peasant women

As explained by Leire Milikua Larramendi (2022), ‘XX. Until the second half of the 20th century, the main currents of feminism stood out in the academic discourse and in the social debate, believing that what had been considered universal was applicable in any context, with a very concrete model of woman: white, middle or upper class, western… and urban”, and in 2010

«A feminist fusion around food sovereignty on the occasion of the passage of the Women’s World March by Euskal Herria, for example, bringing peasant women and feminisms, (…) and the Etxaldeko Emakumeak group, who want to spread the proposal of food sovereignty to feminist organizations, agroecological practices and the impact on the rural environment, as well as contagion feminist movements. Initiatives and meetings promoting the creation of networks and alliances between women in rural, rural and urban areas are very interesting».

In order to respond to the reality and needs of peasant women, the first groups of peasant women emerged in the 1990s: In Gipuzkoa, the Association of Peasant Women EBEL was created in 1991 at the initiative of some peasant women who were part of the EHNE union. In the Alavesa Plain, Tours Soroa was created in 1995. Four years later, in 1999, the Rural Women's Network of Álava was born and in Bizkaia, Amorebieta, Landa XXI, belonging to AMFAR3.

In the second half of the following decade, in 2007, Hitza was born in Gipuzkoa, Urola Kosta, to pay attention to the health and care of rural women, as explained on the web:

«Historically, rural women have not taken place to express experiences, difficulties, fears, joys and anxieties related to their role in the community. They know that their work is the care of the family members of the household, but in many cases they are not aware of the need to take care of themselves and stay out of fatigue and weakening, due to the daily work of the household»4.

Etxaldeko Women5, for its part, was born in 2012, combining the demand of women farmers, sustainable agriculture and the defence of food sovereignty, claiming recognition of the role of women in agriculture:

«women linked to organizations and groups promoting sustainable agriculture denounced the situation of inequality experienced by women in the primary sector. At the same time, they claimed the historical role played by these women in the production and transformation of food and in the transmission of knowledge and peasant culture»6

In 2015, taking advantage of the passage of the caravan of the World Women's March by Euskal Herria, the opportunity was taken to strengthen the visibility of peasant women and join the feminist movement to establish new alliances.

2.4. New rurality, sustainable life and women

The term neorural is used to refer to the installation in the rural environment of a group that comes from urban centers, especially young people. These people are also known as ruralists or artisans depending on their agricultural or craft activity. However, this return to rural areas is not similar in volume to the rural exodus that emptied rural areas (Nogué i Font, 1998). According to Paula Escribano Castaño (2020), this new neorrurality drives a more sustainable model of society in the face of the neoliberal model and tries to live in an environmentally friendly way. It is not surprising, therefore, that women are, to a large extent, the protagonists of this return to the rural environment, abandoned by the lack of opportunities that excluded them from a reproductive role in order to regenerate. This new rurality is due to the crisis of care and the aging of rural societies, where women play an important role linked to a new life model7.

Joan Nogué i Font (1998, 153) distinguishes three major types of new rural: first people engaged in crafts, then those engaged in agriculture and livestock farming and, thirdly, those who, instead of specializing in a given activity, have multiple activities and can include the paid activities they performed in the city. But without a doubt, this author emphasizes the new territoriality linked to this new rurality, in the face of the ignorance of industrial societies, generating standardized and homogenised landscapes. In this sense, work is one of the fundamental elements of this territoriality; facing the specialization aimed at increasing the productivity of industrial society,

«self-employed work linked to land or crafts aims to break the logic of the fragmentation of the urban system through a greater relationship with the environment, a complete productive process, a Community dimension of work that restores social function» (Nogué i Font, 1998:153).

On the other hand, Roberto Torres Elizburu (2006:61), in a negative sense, talks about the counter-urbanization, defines that the rural environment is invaded by people from urban environments and explains that this return to the rural environment occurs in very specific spaces, "they tend to be located in areas well connected and connected with the urban centers (...)". It also considers that ‘the interests and expectations of the new classes, more oriented towards a protective attitude, are in conflict with the developmentalist agricultural interests of the local population’. For Torres Elizburu, this rural renaissance is paradoxically the death of the traditional rural environment, as "the rural environment becomes a valued, demanded and competitive environment for urban societies" (Torres Elizburu, 2006:61).

It combines agriculture, recreational activities, environmental conservation and urban development of the first and second residences. At the same time, gentrification can occur with the arrival of a new social class, with a higher purchasing level, contrary to the developmentalist model and participating in local politics, defending the conservation of this lived environment as a paradise.

This gentrification idea is also found in Ruiz y Galdós (2019:148). According to them, in the Basque Country, the most ‘tertiary municipalities, with a high level of education, with more qualified professions and with higher family incomes, accumulate in the immediate rural environment of the big cities, with environmental and landscape attractions’. Ruiz y Galdós (2019:132) also receive other denominations of this phenomenon such as post-productivism, multifunctionality, counter-urbanization, rural urbanization, gentrification or rural elitization. The term greentrification is also used to highlight the importance of the environment in this process.

Cruz Alberdi Collantes (2016, 2018) stressed that while people who have traditionally worked in the Basque Country in the countryside have decided to abandon agriculture or continue intensive production, the new baserritars go hand in hand with what FAO defines as organic or eco-agricultural agriculture, albeit without difficulties, and linked to family exploitation.

2.5. From the myth matriarchy to ecofeminism

One of the ideas rooted in the Basque imaginary is undoubtedly the importance of the lady of the house as a support for the traditional Basque Country, or the idea that Euskal Herria is based on a matriarchy. In this sense, María Boguszewicz and Magdalena Anna Gajewska (2020:37), as recorded in the review of this myth in the film Amama de Asier Altuna, authors such as Andrés Ortiz de Landosés and José Miguel de Barandiaran citan as creators of this concept and "the image of the woman that was repeated in the scriptures of other experts". According to this anthropologist, in the housing environment, women serve cohesion and stability, but always within the roles traditionally assigned to women in Basque society and culture. Therefore, this does not mean that it has power beyond the domestic sphere, ‘beyond being a symbol of femininity, of the earth, to express such essential knowledge for the survival and development of culture’, because the transmission of culture and language also depends on it.

Another concept associated with the return to Earth is ecofeminism. The term appeared in 1974 with the help of Françoise d'Eaubonne, facing the need to return to nature to a system of patriarchal and capitalist production; the authors Yayo Herrero or Alicia H. Puleo have included in their texts the different theoretical currents surrounding this concept, opposing the productive use of the patriarchate of nature in the face of respect and the cyclochlogue culture.

2.6. Rural women in the media

Euskal Herria has been represented on numerous occasions with a traditional and romantic image related to the village or rural world. Examples include Au Pays des Basques (1930), directors Jean Faugeres and Maurice Champreux; Around the world with Orson Wells, two of the six films “The Land of Basques and Basque Ball”, by Orson Welles; Plot Sor Leku by André Madre; Errestéston by Fernando.

The researcher Javier Díaz Noci, in his doctoral thesis (1992: 112-113), worked on the creation of journals dedicated to the theme of agriculture in the early twentieth century, mostly specialized in the Provincial Councils of Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia. He collected among others: Baserritar (1904), promoted by the Asociación Campesina Anaitasuna; Alkartasuna, of the Catholic Farmers Federation of Gipuzkoa; Boletín Agropecuario-forestal de la Ecma. The Diputación de Vizcaya, founded in 1958 by Goiz-Argi, Agricultura Suparia de Arantzazu, and years later, the Caserío: La pagina agropecuaria de la sociedad de amigos del caserío (1967-1969), which was followed by Lurgintza, published by the Bizkaia Savings Fund.

There are currently two publications on the rural environment, one in Gipuzkoa edited by Ensure Lurra and the other in Bizkaia by the cooperative Lorra, Ongarri 9, magazines of agricultural associations and cooperatives in Bizkaia, published every six months. Bizi Baratze also publishes weekly newsletter 10.

He has also been present on television; between 1976 and 1978, José Mari Iriondo directed the Euskalerria program from the center of RTVE in the Basque Country. In the ETB public channel, Sustraia has accomplished more than three decades and produced two realities located in the farmhouse or work area: Basetxea (from 2002 to 2008) and Baserri (2021), in which contestants had to pass tests related to the daily activities of the farmhouse. Xaloa Telebista offers Ur eta Lur11

In the 1950s, in more than a hundred parishes of Hego Euskal Herria, small radios closely linked to the rural environment emerged. These popular radios provided useful information for the life of the farmhouse, such as those related to the harvest or those related to meteorological information, prices and cultural traditions and Basque rural sports (Gutierrez Paz: 2011). In 1956, the radio Voz de Guipúzcoa, called Movimiento, was inaugurated in San Sebastian. In his programming he offered a session in Euskera by José Miguel and Don Antonio, Enrike Zurutuza and Manu Oñatibia. The latter represented some of the concerns of the baserritars, while giving advice related to their activity.

At present, Bizkaia Irratia and Herri Irratia, who continue to live alongside the Segura and Arrate broadcasters, continue to offer programmes aimed at these baserritarras. For example, in Bizkaia Irratia there is a special section devoted to news on agriculture and fisheries (Fisheries and Agriculture). The Landaberri program on environmental and agricultural information is offered in the Basque Country, under the direction of journalist Arantxa Arza and with the advice of Jakoba Errekondo. In this space, more than professional farmers, useful information is provided for these people who work a vegetable garden. Together with the idea of sustainability and ecofeminisms, we can find in the radio stations programs that transcend the idea of Basque agriculture and that have an internationalist component, such as the Lekil lum – the good land in the Tzotzil and Celtal languages – of 97 stations in Bilbao, or the one that performs the association Lur eta murmur Bizilur in the radio Xorroxin, which leads by title 12.

On the other hand, in 2020, Mendialdea Radio was born in Álava and its objective is to end, from the culture, with the rupture existing between the city and the rural environment, or, as indicated on its website, "from the Alavesa Mountain, by updating the rural narrative, closing the conceptual gap. Always through culture”13

Although there are some podcasts related to agriculture, the Light and the Gardens of Life perform two podcasts: Sedup14 and Doble Menda15. In 2022, EITB published eight episodes of Subtraction podcasts, which today can be heard to its liking.

In the sessions and in the media mentioned, although peasant women appear, they have no place of their own, but there are some documentaries that give rural women their own voice:

Maitane Arnaiz Etxenausia and Leire Urkidi Azkarraga led Earth, work in 2015. Voice of baserritarras women from Usurbil 17.

Tierra 18 (2018) female is a documentary about women producers and food sovereignty in Navarra. It collects testimonies from five women from the primary Navarro sector, their reality and demands. Iñaki Alforja, promoted by Mugarik Gabe Nafarroa, Mundubat and the IPES Foundation.

Peasant women from different generations have gathered testimonies in the documentary Erroa eta geroa19 (2020). Experiences, concerns and reflections join the past and the future. Directed by Itziar Bastarrika and Ainhoa Olaso, conducted by a group of women named Sorgintxurrak within the Baserritik Mundura course.

Another documentary shows the experiences of rural communities in Andia (2021) and 21 videos have been published on the EHNE website under the title Transmitting the wisdom of peasant women, as well as the Meetings of Peasant Women and in the Caserío We are a Revolution! graduates.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research object

The purpose of this study is to analyze the visibility of women in the Sustraia program on the primary sector produced by EITB.

Sustraia

Over three decades ago, Sustraia was born with the objective of providing the latest information on the primary sector, with special attention to the promotion, innovation and new generations of the primary sector. In Basque on Saturdays at 12:30 in ETB1 and in Spanish at 11:45 in ETB2. Each session lasts 30 minutes. In addition, you can see the letter and most seasons are collected on the EITB website https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/57/.

Technical details:

Screenplay and Direction: Josu Butron

Production delegate: Maite Etxebarria/Elena Gozalo (from 2018).

Production by ITESA for EITB.

Program duration: 30’.

Structure: Report 1 - Shorter news – Report 2 (in some seasons special mention was made of innovation in the last section).

3.2. Research objectives

This study aimed to analyze the visibility of rural women in the Sustraia program that EITB offers on the primary sector, with the support of the Deputies of Bizkaia, Araba and Gipuzkoa. The following measures have been taken:

- Presence of women: the presence of women in the sections studied is analyzed, as well as the role of the women present (expert, expert, student, political representative, union or association). That is, a quantitative and qualitative research is carried out.

- Gender perspective in information: whether or not information on the natural situation of rural or rural women appears.

- Gender stereotypes: whether or not a stereotyped image of rural or rural women is provided.

- Values attributed to the rural environment and to the women in it present.

3.3. Sample and sheet

On the EITB website we have made a selection of on-demand sessions and analyzed 18 sessions or sections of the years 2015-2023. Two of each year have been chosen for their election, one of the beginning of the year and another of the months after the interruption of the summer, advancing the date one month each year. In some cases, there is no issue at the corresponding date, the following section is analyzed. Therefore, the following sessions have been analyzed:

|

Year |

Date of issue |

URL |

|

2015 |

4 April |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/abra-sariak-idiazabal-gazta-valorlact-eta-bizkaiko-txakolina/osoa/5042/92505/ |

|

12 September |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/iturrarango-haritz-bilduma-arabako-txakolinaren-uzta-eta-lehen-sektorea-berrikuntza-bidean/osoa/5042/92518/ |

|

|

2016 |

7 May |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/alimentaria-2016-eta-miren-patata/osoa/5500/113944/ |

|

9 October |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/urriko-lehen-astelehena-eroski-esnea-eta-paturpat/osoa/5500/113953/ |

|

|

2017 |

3 June |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/nekazaritza-eskolak/osoa/5789/129030/ |

|

11 November |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/aiako-testaje-zentroa/osoa/5789/129038/ |

|

|

2018 |

24 February |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/agerre-baserria-baratze-eta-fortaleza-kafea/osoa/6055/144941/ |

|

15 December |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/itsasoko-hondakinak-eta-kalikolza-proiektua/osoa/6055/144970/ |

|

|

2019 |

2 March |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/azienden-elikadura/osoa/6374/157696/ |

|

12 October |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/urriko-lehen-astelehena-getariako-txakolinaren-mahats-bilketa-eta-kortaria-gaztandegia/osoa/6374/157713/ |

|

|

2020 |

4 April |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/ibaigane-jatetxea-juananeko-borda-eta-zubillaga-hiltegia/osoa/6724/174369/ |

|

7 November |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/garlan-lekariak-hareko-eta-lana-scoop/osoa/6724/174387/ |

|

|

2021 |

8 May |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/10-atala/osoa/7450/187816/ |

|

4 December |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/30-atala/osoa/7450/187836/ |

|

|

2022 |

4 June |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/15atala/osoa/8081/202286/ |

|

24 September |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/17atala/osoa/8081/202288/ |

|

|

2023 |

25 February |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/1atala/osoa/8621/219331/ |

|

7 October |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/19atala/osoa/8621/219350/ |

A factsheet containing the characteristics of the people attending these sessions was prepared, which included the following sections:

- Physical dimension: name, age and gender of the person interviewed.

- Social dimension: social relations, civil status, profession and education.

- Local dimension: where the person is: at work, at home, abroad…

- Plot dimension: reason for participation in the session (producer, expert, witness…)

Although this analysis allowed obtaining sufficient data on the visibility and gender perspective given to women in the session, the study is completed with the reports offered in Sustraia around the Rural Women's Day celebrated on October 15. At the following meetings22:

|

Date of issue |

URL |

|

2015-10-24 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/giez-berri-eta-landa-eremuko-emakumeen-eguna/osoa/5042/92524/ |

|

2016-11-19 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/euskal-sagardo-jatorri-izendapena-sasi-ardi-eta-landa-eremuko-emakumeak/osoa/5500/113959/ |

|

2016-12-03 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/haria-galtzen-bizkaia-txakolina-forum-eta-emakumeak-euskal-landa-eremuan/osoa/5500/113961/ |

|

2017-10-21 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/landa-eremuko-emakumeen-eguna/osoa/5789/129035/ |

|

2018-10-27 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/arabako-txakolinaren-mahats-bilketa/osoa/6055/144963/ |

|

2019-10-26 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/euskal-oiloa-landa-eremuko-emakumeen-eguna-eta-bizkaiko-txakolinaren-mahats-bilketa/osoa/6374/157715/ |

|

2020-10-17 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/larreako-gaztak-landa-eremuko-emakumeen-eguna-eta-arabako-errioxako-mahats-bilketa/osoa/6724/174384/ |

|

2021-10-23 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/24-atala/osoa/7450/187830/ |

|

2022-10-22 |

https://www.eitb.eus/eu/nahieran/dibulgazioa/sustraia/21-atala/osoa/8081/202292/ |

4. Analysis of sessions

4.1. Greater prominence of men

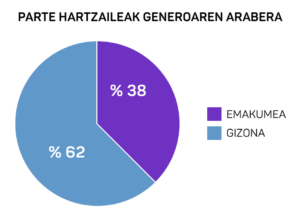

The chart above shows that of the 154 people who expressed in the 18 sessions analyzed, 58 were women (37.67%) and 96 men (62.33%). There are other protagonists, some of them with names and surnames (honoured, awarded, actors…), but in this analysis we have not taken them into account and have analyzed in particular the profile of those who take the floor.

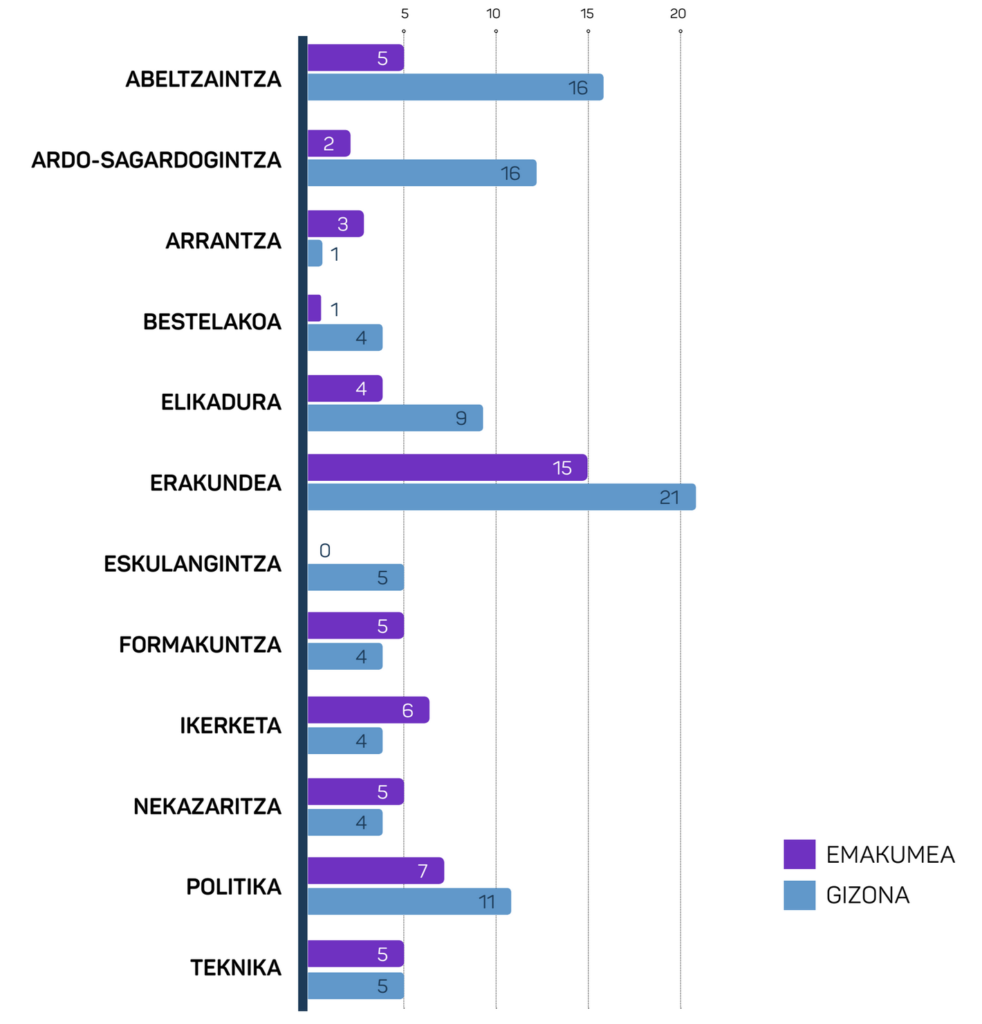

In a more comprehensive analysis of the profile, we divide the representation of women and men by area, taking into account the main activities related to the rural environment: livestock (including cheese and meat sales), wine and cider production, food (food marketing and gastronomy), crafts and agriculture. Representatives of private and public entities (associations, foundations, etc.) have also been classified. and political representatives of the foreign and government deputies. We have also distinguished between technicians (veterinarians or inspectors, for example) and researchers. Likewise, although the objective of this study is to investigate the presence of women in the rural environment, companies and people engaged in fishing in the first active sector also appear in Sustraia, which is why they have been included in our study. Finally, in the area of Others, people who are not directly related to the rural environment have been classified as actors or athletes. This distribution is closed by those who work in training.

4.2. Representation of men and women by activity

The graph above shows the number of men and women related to each area or activity:

- The representation of women in fisheries and agriculture is greater than that of men; in the first case, linked in particular to the marine canning industry.

- As for the food industry, it should be noted that all the professional cooks in the sections studied are men, although in many cases they are women. Also in this area, the workshops focus on working women (resource videos).

- The presence of women in research (60%) and training (55%) is somewhat higher, while in the technical profile parity is total. In other words, there is parity when it comes to interviewing the experts participating in the session.

- On the other hand, the participation of men in livestock farming (76.2%) and in wine, txakoli and cider production (85%) is even higher than that of women. There are no women in the craft sector alone.

- As in other sectors, women are increasingly represented in the public and institutional spheres and 61% of the political representatives participating in the sessions investigated are men, 54% in the other organizations.

4.3. Profile of women who appear

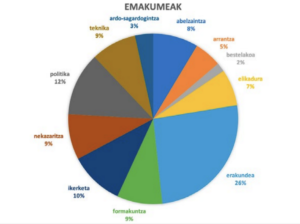

38% of the 56 women in the study are institutional representatives (in the case of men the percentage is slightly lower, 34%), both from private or public institutions and from the government, that is, from political activity. In addition, the technical or knowledge profile of women (28%) stands out, with 34% of professionals related to rural areas. In the case of men, almost half (49%) are engaged in a trade related to barn, especially in the field of livestock, wine and cider.

It should be noted that in most videos offered during the program, men and women appear. It is more difficult to see women and often only men. Maider Martínez is one of the protagonists of the session of 24 September 2022 and the vice-president of the Idiazabal Designation of Origin. It had no prior relationship with either agriculture or livestock, and has been trained at the Arantzazu Pastors School. She says that "being a woman here and being young can be a model for others. The news coming into the sector today is not the same news that was incorporated twenty, thirty or forty years ago, the model is very different».

On the other side is the food industry, where more women appear. It is an exception in the news of hospitality related to food. For example, in the 4 April 2020 report on the restaurant Ibaigane, four women dressed in white aprons work in the kitchen (meat, cutting vegetables…), but the man, the only one who appears by surname, Aitor Maguregi dressed in black, speaks of the restaurant. To reinforce the stereotyped image of this professional cook man with his own name, this also exalts the mother as a reference. Also, in the performance of May 8, 2021, in the words of Aitor Arrangi, of the restaurant Elkano de Getaria, we also find the image of the woman who cooks (grandmother) and the parrillero who worked in the public sphere (professional cook): “We are in the restaurant Elkano, in the house of her father, Grandma Josepa was good cook and in her house a small restaurant.

4.4. Scenarios and designations

Regarding the scenarios in which the interviews or statements of experts and experts participating in the program are collected, there are also no significant differences according to gender; except for all politicians and some institutional representatives, the people who appear appear appear in their workplace. In some cases, although not active, they appear in work clothes.

Often the driver of the program explains the names of the protagonists, without surnames, and in the subtitles there is a surname, except Oihane Cabezas Basurko, which appears on December 15, 2018. Although this mention with proper names was initially interpreted from a gender perspective, in view of all the sessions, it is evident that there are no great differences in the appointment of women and men and can be interpreted as a strategy of affective proximity to people.

In the subtitles there are also no particularities depending on the gender, and in most cases under the names and surnames the reference is made to the farmhouse, farm or institution; the function is concrete in the case of political positions, even some technicians. It makes no reference to anyone's personal situation, although the speaker sometimes explains the relationship between the people who appear, especially kinship.

4.5. New rurality

Well-being, better life, healthy eating, nervousness drawn by the urban center, abandonment of the stressful profession, new opportunities opened by unemployment, need to reconcile family and work life, offer children a sustainable relationship with nature and the environment, maintain and renew the family tradition… These are some of the values that appear throughout the sessions of women who have decided to live and work in the urban environment, leaving behind the center.

On October 9, 2016, Irene Arnaiz, of the SC cooperative Casanueva, after explaining that her husband Jon Gutierrez had taken over the exploitation of her parents, explains that she started as follows: “After being a daughter I started(…). Here's a lot of work and help was needed. I really like work and I'm happy. If you don't like it, you can't work here, clearly. We like to live here and live from our work. I teach my children to love and care for nature and animals.”

Estitxu Sudupe, a producer of beans, is also an example of this rurality, is considered a street child and associates agriculture to a healthy diet, to well-being: «I always liked agriculture, I liked to eat the harvested... and as a consequence of being a mother, I started to reflect on organic farming (what we eat)...» Therefore, he took courses and started planting beans, in which he had the support of the neighbors and also of the association of producers of beans, of which he is a member.

In the April 4, 2020 session, Jone Etayo explains that he was from Pamplona and that when he began he did not know the profession, but left the city centre with problems in his workplace. She says she was surprised by the “fascination” of this homemade work that asks a lot, but it seems a lot, although she acknowledged that the beginning was hard.

In the session of June 4, 2022, Aintzane Garmendia appears in the garden with her partner and young child, and in the arms, in the charcuterie. He also links rurality to family reconciliation. He received from the grandfather of Caserío Argaia and during the pregnancy his third son left his job as a commercial in construction.

Among these new peasants, it is worth noting the presence of Colombian lawyer Marcela Pava in the program of September 24, 2022. She manages the Huerta Mustai with her partner and is the only migrated woman who has appeared in the sessions analyzed 23.

4.6. Women “entrepreneurs” and “exemplars”

At the session of 11 November 2017, in the report on the Ekoudalatx Seminar, the speaker stated that ‘Idurre and Nerea are young women who perfectly meet the profile of Basque women in rural areas’, but do not explain what that profile is.

On the occasion of Rural Women’s Day, at the session on 15 October 2015, the programme focuses on the actions of two women who participated in the institutional event: ‘those who represent the combative spirit of rural women’. On the one hand, the values that fit Iratxe Martinez, interviewed at the poultry farm in Garai, are: working professionally and reconciling family and work life; innovating as a young and entrepreneurial woman and caring for family and environmental values.

On the other hand, in the tertulia of Loli Casado, of the Bodega Loli Casado, it is demonstrated that, although it is recognized that it is a masculine world, if women work, they can do so. In this case, at a time of the interview, her husband appears next door and talks about the winery. Married parallelism and says that his father, Luis, could not take the hold without the work of Emi, his mother, and now he has the help of Jesus, his husband.

In the session of 19 October 2016, the programme interviews two women working in the public sphere; Maite Aristegi, a union and political worker; and Ana Villasante, Mayor of Bernedo. It should be noted that in both cases women are performing “domestic tasks”. In the case of Aristegi, cleaning the farmhouse he manages and in the case of Villasante, shopping before going to have coffee.

Elburg Mayor Nati López de Muniain stars the report on Rural Women’s Day, which was held on 21 October 2017. He denounces that the Basque Country has always associated itself with the matriarchy, that the woman ruled the house inside the house, but that the property was of the men, that there were limitations to place the farm in the name of the women. She believes that women make other kinds of policies.

In the interview on October 17, 2020, Marta Mas, a tourist who leaves the city and moves to Bernedo, is presented as an entrepreneurial woman. Before starting the talk, the kids show up with the school bus and then shopping in the butcher's shop. The new rural relates life in the Alavesa Mountain with well-being, family and good eating, with the possibility of realizing the desired life. It has created the theatre company and the radio Mendialdea, because of the importance of culture also in the workplace.

In the session of October 23, 2021, Arantxa and Ana Eguzkiza, “the two female entrepreneurs” of the Iparragirre Plantation of Hernani, are mentioned. In presenting Arantxa Eguzkitza, president of the Association of Sidreros de Gipuzkoa and the Association of Organic Agriculture of the Basque Country, he also stressed that it was “dynamic”, “exemplary woman” and added that “these are increasingly the positions of responsibility of the primary sector”. For her part, Eguzkitza points out the importance of women participating in institutions “Not because they are women, but because of their value, dedication and commitment, women have also gained prominence in the primary sector”.

This idea that more and more women are needed in the public sphere is also found in other testimonies:

According to Aristegi: "Women need to be involved in society! And to lead socially, to tell the problems we have and make the demands… We have to face the problems of self-esteem. We know it, we make proposals…” (Sustraia, 19 October 2016).

In the session of December 4, 2021, we inform of the event of CertainLurra - Sowing the Future, in which people from urban and rural areas are to meet each other. It involves footballer Aintzane Encinas, who emphasises the place that women should occupy, equating with what happens in sport: ‘we have seen that girls also have our place, both in football and in the primary sector, and it seems that today’s congress and girls are also there, that there have been many changes and that girls have room in the primary sector, in sport and in any sector’.

4.7. Praise for the Women's Institutions and Statute Act

During the session, which was held on 24 October 2015, as part of the celebration of Rural Environment Day, Elena Unzueta, a member of the Provincial Council of Bizkaia for Sustainability and Natural Environment, commented in her message the recent adoption of the Statute for Women Farmers of the Basque Country, and in that idea the other representatives of the government were added to it.

The statutory theme reappears on 27 October 2018, starting from that three-year limit, to receive subsidies, as the institutions are obliged to include women in management, and two main lines are indicated: (a) ownership of the farm is also on behalf of women (34%) and (b) that women are represented in entities of the primary sector.

This law was also the subject of debate in the program of October 26, 2019, in which the words of representatives of various institutions are collected and reference is made to the experience of Raquel Ramírez in the association El Colletero de Nalda. The speaker concluded by saying that much remains to be done and stressed that ‘the work and participation of females is indispensable’.

4.8. Hala ere, stereotype “feminine”

The most stereotyped images of women were also found in the reports on Women's Day in Rural Areas. Although most of the participating women are older, they are not interviewed in any session. In the first session analyzed around the celebration, the announcer states that “these were stories that particularly shocked the audience” about the experiences of seven exposed women, and that “they demonstrated that to make dreams come true, work and imagination are needed”.

As already mentioned, in the session of October 19, 2016, Maite Aristegi performs the cleanings of the farmhouse he manages and Ana Villasante makes the purchases before taking a coffee. On October 17, 2020, Marta Mas, a bodybuilder who has left the city and gone to Bernedo, before starting the talk, appears accompanying her children to the school bus and then shopping in the butcher shop.

In the session of 22 October 2022, on Oneka Zaballa, who governs the Fidel Abans de Dima estate and works as a lawyer with the Landa XXI association, the announcer says that “Oneka mimics animals and adapts perfectly despite being young”. The comment also highlights the truth.

5. Conclusions

Regarding the percentages, and with the parity established by the Research Group Visibility of Women in the Media 40/60, we can say that the presence of women in Sustraia is close to parity, since almost 38% of the experts and busy interviewed are women. However, given that the report prepared by the government in 2020 states that women represent 49% of the population living in the Basque rural environment, we can say that there is still a way to go to increase the presence of women. It is true that not all the inhabitants of rural areas work there, and that the percentage of women working in the primary sector is three points lower than that of men, so we can say that in the sitting we are trying to make women appear.

As in other areas, most of the women who appear are institutional representatives with public experience, accompanied by technical profiles (experts). On the other hand, it should be noted that women who have traditionally participated in the household (the elderly who have been invisible) have no voice, although both political and institutional representatives and women of new generation insist on the need to recognize their work and trajectory. It is noteworthy that despite the presence of these older women in the reports of Women's Day in the Rural Environment, they have never been given the floor. As I say, their references are always cross-cutting.

In relation to the previous idea, when choosing exemplary women in rural areas, there are those who often work in the public sector or have succeeded in their sector, entrepreneurs. In the case of men this is not so obvious and curious men appear that have not had special achievements.

On the other hand, there is no gender distinction when naming or placing the protagonists, nor do they appear in stereotyped roles, although there are some gestures that stand out in some sessions: for example, there are women who appear next to a man who speaks, this does not happen the other way; while the man who works the kitchen is represented, when women cook, they appear in the private sphere (in the kitchen) and in the imaginary. There are also women who work in public spaces, cleaning, care or house-related activities.

The lives of rural women are related to well-being, healthy eating, sustainability or respect for nature, and in this sense the need for women from the city center to contribute life and work and a healthy environment to their families is seen. Also, many of the women who appear present values related to the values of ecofeminism, even those who have opted for ecological exploitation. It should be noted that in the sessions studied there is a constant commitment to extensive livestock and farms that respect nature. The quality, health and sustainability values of seasonal zero kilometre products are also praised, along with innovation and technology. This also explains why young producers play a greater role. However, as I say, this gives a distorted image of the rural environment, which hides the backward struggles, including the feminist struggle.

We must not forget that this programme is part of an agreement between the public administrations of the CAPV and EITB, and that a paternalistic view of these institutions is often expressed, especially when it comes to recognising women’s work. Recognition of the work done by previous women and the need to attract young people to the primary sector are some of the aspects frequently explained by political representatives, but the session presents as the main instrument the status of rural women approved in the CAPV, along with the commitment and will of women. There is no presence in any session of the feminist movement organized in rural areas. This should therefore use other means to socialise your messages.

The discourse also warns of the lack of feminist vision in many issues and, in many cases, projects a very romantic image of the peasant woman, brave, with great work capacity and transmitter of a culture rooted in the Basque roots, which relates the traditional idea of matriarchy with the future based on innovation.

6. Bibliography

Aguirre, Estela y Muñoz, Rebeca (2016): La ‘neorruralidad’, ¿liderada por mujeres?El País, 14 octubre 2016, en https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/10/14/planeta_futuro/1476454833_494104.html [Azken sarrera: 2023ko ekainaren 20].

Alberdi Collantes, Juan Cruz ( 2018): Lurrarengan interbentzioa, ezinbestekoa burujabetza garatu nahi duen elikadura eredu batentzat; Lurralde: invest. espac., 41, 43-67 o.

Alberdi Collantes, Juan Cruz (2016): Elikadura burujabetza eta nekazaritza ekologikoa Donostian; Lurralde: invest. espac., 39, 299-322 o.

Andere Nahia (2021). Quelle place pour les femmes dans l’agriculture en Pays Basque Nord? Étude sociologique, http://anderenahia.asso.fr/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/202109_Ensemble_parlons_Egalite_paysanne.pdf.

Arozamena Ayala, Ainhoa. Goiz-Argi. Auñamendi Entziklopedia [on line], 2023. [Azken sarrera: 2023ko martxoaren 24a], https://aunamendi.eusko-ikaskuntza.eus/eu/goiz-argi/ar-66867/

Arrea (2021) “Emakume ekoizleak eta Elikadura Burujabetza Nafarroan generoaren ikuspegitik”, https://arrea.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Emakume-ekoizleak-eta-elikadura-burujabetza-Nafarroan-generoaren-ikuspegitik-final.pdf.

Artola Arin, Leire (2023): Emakume baserritarrak, funtsezkoak bezain ahaztuak, Bizi Baratzea, 2023ko urriaren 15a, https://bizibaratzea.eus/albisteak/astekaria/2842/emakume-baserritarrak-funtsezkoak-bezain-ahaztuak.

Boguszewicz, Maria; Gajewska, Magdalena Anna (2020): El matriarcado gallego, el matriarcado vasco: revisión del mito en Matria de Álvaro Gago y Amama de Asier Altuna, Madrygal 23 Núm. Especial (2020): 35-50, Revista de Estudios Gallegos ISSN: 1138-9664 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/madr.

Díaz Noci, Javier (1992) : Euskal prenstaren sorrera eta garapena (1834-1939). Tesis doctoral; en http://www.euskara.euskadi.net/appcont/tesisDoctoral/PDFak/Javier_Diaz_Noci.pdf [Azken sarrera: 2023ko apirilaren 7], 112-116 o.

Eaubonne Françoise d’ (1974): Le Féminisme ou la mort, Paris, Pierre Horay.

Etxaldeko Emakumeak eta Durangoko Berdintasun teknikariak (2019). Kontuan hartu gaitzaten, https://bizilur.eus/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/KONTUAN-HARTU-GAITZATEN.pdf.

Etxalde (2021): Legeen azterketa ikuspegi feministatik, https://etxaldeko-emakumeak.elikaherria.eus/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/EMAKUME-BASERRITARREN-LEGEAK-LUZEA.pdf

Eusko Jaurlaritzako Landaren eta Itsasertzaren Garapeneko eta Europar Politiketako Zuzendaritzako Estatistika Organoa (2022): Emakumeak Euskal Landa Eremuan (txostena): https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/documentacion/mujeres_rurales2020/eu_def/adjuntos/Mujeres-en-el-Medio-Rural-Vasco-2020_eu.pdf.

Richard, Frédéric; Dellier Julien et Tommasi, Greta (2014): Migration, environnement et gentrification rurale en Montagne limousine, Journal of Alpine Research, 2014 102-3, https://journals.openedition.org/rga/2525.

GoiBerri (2016): EBEL, 25 urte borrokan, Goiberri, 2016-12-27, https://goiberri.eus/2016/12/27/ebel-25-urte-borrokan/.

Gutiérrez Paz, Arantza (2011): “Irrati-hitza, Jangoikoaren berba: Herri irratietatik Radio Mariara”; The radio is dead, long live the radio!, Actas del I Congreso Internacional de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad celebrado en Leioa el 24 y 25 de noviembre de 2010, p. 478-488.

Herrero, Yayo (2015): Apuntes introductorios sobre el Ecofeminismo, Centro de Documentación Hegoa Boletín de recursos de información nº43, junio 2015, https://boletin.hegoa.ehu.eus/mail/37 [Azken sarrera: 2023ko ekainaren 15a]

Homobono, José Ignacio (1991): “Ámbitos culturales, sociabilidad y grupo doméstico en el País Vasco”; Antropología de los pueblos del norte de España, Universidad Complutense de Madrid y Universidad de Cantabria.

Lopez Marco, Lucía eta Sánchez María [Leire Milikua Larramendiren itzulpena] (2020): Lurre(z)ko ahizpen feminismoaren alde: landa-eremuko emakumeen aldeko 2020ko Manifestua, Mallata, https://mallata.com/lurrezko-ahizpen-feminismoaren-alde-landa-eremuko-emakumeen-aldeko-2020ko-manifestua/ [Azken sarrera: 2023ko azaroaren 15]

Martínez Montoya, Juantxu (1998): Cutura, identidad y cambio social. Los procesos de reidentificación cultural en el medio rural del País Vasco; KOBIE (Serie Antropología Cultural). Bilbao, Bizkaiko Foru Aldundia-Diputación Foral de Bizkaia N.º VIII, pp. 55-65, 1997/1998.

Milikua Larramendi, Leire (2022): Lur gainean, itzal azpian (Emakume nekazariak eta parte hartzea), LISIPE, Susa.

Noguè i Font, Joan (1988): El fenómeno neorrural, Agricultura y sociedad, Nº 47, 1988, 145-175 o.

Pascual Rodríguez, Marta; Herrero Lopez, Yayo (2011): Ecofeminismo, una propuesta para repensar el presente y construir el futuro, publicado en Boletín ECOS nº 10 (CIP-Ecosocial), de enero-marzo 2010, en www.madafrica.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ecofeminismo_una_propuesta_para_repensar_el_presente_y_construir_el_futuro_Marta_Pascual_y_Yayo_Herrero_2010.pdf [Azken sarrera: 2023ko ekainaren 10].

Puleo, Alicia H. (2001). Luces y sombras del ecofeminismo. Asparkía. Investigació Feminista, (11), 37-45, https://www.e-revistes.uji.es/index.php/asparkia/article/view/904.

Torres Elizburu Roberto (2006): La contraurbanización en la Comunidad Autónoma del País Vasco, Lurralde: Investigación y espacio, ISSN 0211-5891, Nº 29, 2006, 57-85 o.

Ttipi-Ttapa (2020): Amaia Iturriria: Egun emakume nekazariak ez dira soilik nekazarien andreak, 2020ko uzt. 24a, https://erran.eus/baztan/1595341979260-egun-emakume-nekazariak-ez-dira-soilik-nekazarien-andreak.

Valle Murga, María Teresa del (1983): “La mujer vasca a través del análisis del espacio: utilización y significado”, Lurralde: Investigación y espacio 6, 251-270 o.

1 MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033/ eta FEDER A way to make Europe direlakoek finantzaturiko “New rural imaginaries in contemporary Spain: culture, documentary and journalism” (PID2021-122696NB-I00) ikerketaren barruan kokaturiko ikerlana da hau.

2 https://gardentasuna.bizkaia.eus/documents/1261696/11861170/CONVENIO+SUSTRAIA.pdf/25f4df77-0daa-97e1-4958-6234d4b61d6f?t=1651576632975.

5 https://etxaldeko-emakumeak.elikaherria.eus/eu/

6 https://etxaldeko-emakumeak.elikaherria.eus/eu/gu/

7 https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/10/14/planeta_futuro/1476454833_494104.html

8 https://www.fao.org/family-farming/themes/agroecology/es/

9 https://lorra.eus/categoria/ongarri/

11 https://xaloatelebista.eus/gure-saioak/ur-eta-lur/

12 https://erran.eus/irratia/Ur_eta_lur

13 https://www.mendialdearadio.com/

14 https://bizibaratzea.eus/multimedia/egonarria

15 https://bizibaratzea.eus/multimedia/menda-bikoitza

16 https://www.eitb.eus/eitbpodkast/bizitza/jan-edana-baratza/sustrai/

17 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9TlrCItTIHY

18 https://www.navarraecologica.org/eu/periodico-navarra-bio/nafarroako-emakume-ekoizleen-borroka

19 https://www.argia.eus/multimedia/dokumentalak/erroa-eta-geroa

20 http://www.guesalaz.es/eu/documental-mujeres-rurales-de-andia-disponible/

21 https://www.ehnebizkaia.eus/eu/bideoak/

22 No sessions on Rural Women’s Day were held in October in 2023, while two spaces were offered in 2016, one of them in the December 3 issue.

23 Among the alliances maintained by the women of Etxalde, they work for the visibility of migrated women in the Basque rural environment in programs, conferences, and programmed publications.