In parallel to the era of digitalization, the new Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have generated constant changes in the media’s newsrooms, conditioning all journalistic processes, especially access to data, sources and information, information processing, writing, production, editing and dissemination and contact with the public. These changes, therefore, have also changed the epistemology and self-vision of the profession for more than three decades, the training of journalists and the scientific analysis of journalism (Meso, 2003; Peña-Fernández, 2005).

1. Introduction

In this evolution, after the computerization of newsrooms in the seventies and eighties, the most famous landmark was the emergence of web technology in the nineties. This changed some of the most characteristic features of journalistic activity, such as the processes of collaboration between professionals and contact with sources. In addition, new languages and narratives for content creation (multiplatform, hypermedia, interactive multimedia and transmedia) and distribution processes (immediacy) were introduced.

These developments gave rise to a generic journalistic profile known as a “cyberjournalist” (Palomo, 2004), with the ability to work and edit content in many formats, as well as specialized profiles (multimedia journalist, data journalist, SEO journalist, etc.). ). In this development line, the leap of the media to pioneering social networks, such as Facebook (2004) and Twitter (2006), generated other demands in the line of community management and public participation management (Mendigaz-Galdospin and Meso-Aymedio, 2016), as well as in the line of information production according to the characteristics of these social platforms.

In the Basque professional context, the arrival of the website generated the first analyses on adaptation in the main press, radio and television media (Díaz-Noci et al., 2007; Meso-Aymedio et al., 2005; 2011). Subsequently, and given the changing nature of the journalist’s technology and work environment, the profile of this profession has had to be reviewed and investigated periodically (Larrondo Ureta and Peña-Fernández, 2024).

In fact, the media companies have continued the technological evolution marked by the paradigm of continuous innovation, in many cases starting from specific departments and innovation laboratories or Medialab (Larrondo Ureta, 2017). In this regard, as reflected in the book Digital profiles of Basque journalists and dialogue with audiences (Pérez-Dasilva et al., 2021), the profession is marked by negative perspectives on working conditions and the economic difficulties experienced by the media, although improvements have been observed in other areas, such as reducing the gender gap in the profession.

The rapid evolution of technologies has set a new milestone and a new need for research linked to the development of artificial intelligence (AI). New research has raised professional objections to the application of this technology. The difficulties in paying and hiring experts to develop AI solutions or the resistance and reluctance shown by some journalists to communicate with the new technology are a source of concern. These attitudes may be based on the perceived threat of professionals working in the reference media (De Lima and Wilson, 2022). In any case, this situation is not entirely new, since it is similar to the period in which information began to spread on social networks, such as the one experienced in the first decade of the new century in the face of the development of convergence processes in the newsrooms of different media (López García and Pereira - Fariña, 2011).

AI is based on the use of algorithms, and its application in media newsrooms has already shown some advantages, such as the automation of data analysis and trends, classification tasks, the organization of information and the distribution of information, the recommendation of contents to users, the verification of information or the improvement of the relationship with audiences using chatbots (Sánchez-Esparza et al., 2024).

Beyond automation, Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAA) has been another step forward that has allowed the transformation of creative processes for the production of texts, images and sounds. This transformation raises legal and ethical questions. With regard to the former, regulatory frameworks related to AI, such as those in Europe, do not specifically mention the media, except in aspects related to disinformation and digital literacy or data, and intellectual property is one of the main challenges in this regard. Regarding ethical questions, editorial independence, media responsibility and the role of journalism in society dominate professional and academic debates (Ufarte-Ruiz et al., 2021). In this regard, it is important to highlight the role that some associations and institutions are playing in regulating this field, such as the pioneer decalogue for the ethical use of artificial intelligence in the media, published by the Basque College of Journalists (2024).

At present, artificial intelligence is expected to transform the role of journalists in order to focus on tasks of local value, while maintaining the task of monitoring and making decisions on the quality of the final content that reaches viewers (Tuñez-López et al., 2021). For this reason, it is recognized that the algorithmic revolution requires new journalistic profiles that combine technological skills with traditional knowledge of journalism (García-Caballero, 2020; Mayoral et al., 2023).

At a practical level, it is necessary for journalists to know how to use the basic tools of AI (free or integrated in the content manager of the environment or CMS) to summarize, rewrite, illustrate, label, SEO, translate or transcribe the video to the text, always in an ethical and transparent way (that is, recognizing the use of this tool). It is important to integrate AI so that information professionals can work with it from editors or worksheets (Bernat, 2024).

For all these reasons, the implementation of artificial intelligence in newsrooms and the media is introducing some complex challenges for journalists and information professionals (Beckett et al., 2023; Danzon-Chambaud & Cornia, 2023). Based on this general situational framework, this chapter provides up-to-date information on the use of advanced technological tools in the newsrooms of the Basque media and helps to clarify the perspectives and perceptions of those responsible for shaping Basque journalism on a daily basis. The data presented under the following headings are derived, in particular, from a study developed in collaboration with the Basque Journalists Association, within the framework of the University-Society projects funded by the University of the Basque Country.

2. Methodology

The objective of this research is to know the use of artificial intelligence in the newsrooms of the Basque Country. For this purpose, interviewing professionals in action has been carried out.

The survey was conducted online in May and June 2024 and was supported by telephone. A total of 501 responses were collected from journalists and media workers working in the media, companies or institutions of the Basque Country. The participants were selected from the data provided by the Basque Government Open Communication Guide (https://gida.irekia.euskadi.eus) and the records of the Basque Journalists Association.

For the study, the anonymity of the respondents was guaranteed. Among the participants, 276 were men (55.1%), 223 women (44.5%) and 2 people were identified in other caegories (0.4%). Other variables were also taken into account, such as the years they have worked, the tasks they carry out, and the type and scope of media or institutions in which they work.

3. Results

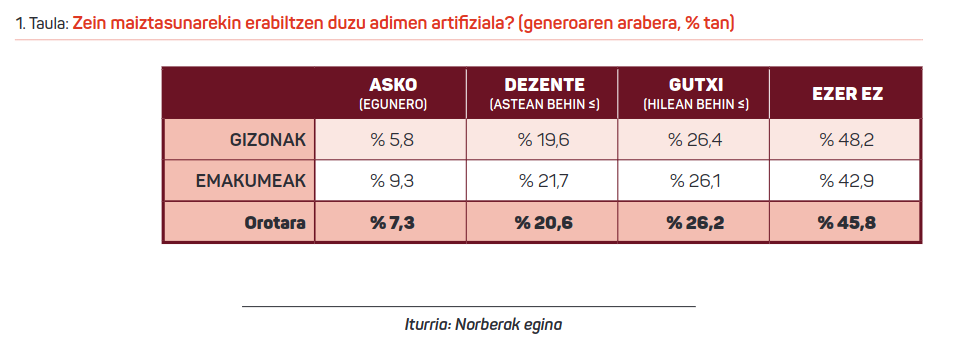

Firstly, the measurement of the use of artificial intelligence among journalists and media professionals in the Basque Country indicates for the time being a limited spread of this technology. 45.8% of professionals say they never use these tools in their work, while 7.3% say they use them daily, 20.6% at least once a week and 26.2% at least once a month. Overall, three out of four professionals use artificial intelligence very little in their work.

The survey carried out has also shown interesting trends by gender. Thus, among women, the use of artificial intelligence - from time to time at a minimum - is higher (57.1%) than among men (51.8%) (1. The table). According to these data, it can be suggested that women have been more active in the adoption of this technology, although the use of high frequency (daily) is still relatively low in both genders. In this context, it is essential to identify potential barriers to the use of technology and to encourage initiatives that incorporate a gender perspective.

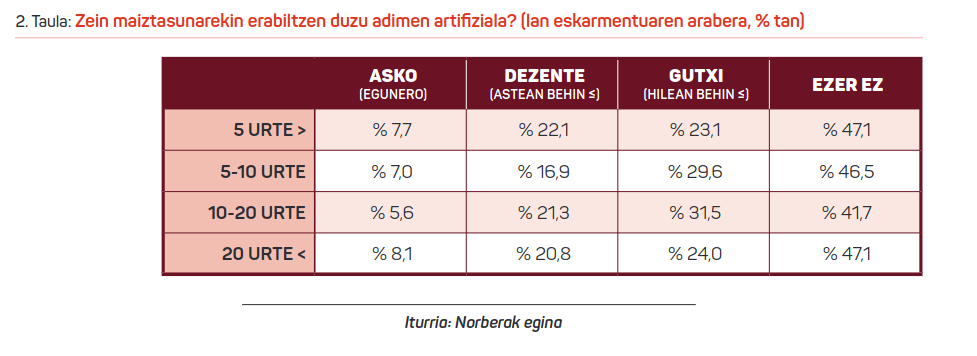

On the other hand, the years of experience in the media according to the data of this survey are not an important variable to explain how professionals are aware of this technology. The experience of the staff does not seem to influence the use of these resources and the results in all groups are quite similar (2. The table). The use of high frequency (daily or at least weekly) is very similar and ranges between 26% and 30%. Therefore, it can be concluded that the usual use of artificial intelligence has not so far depended on the level of experience, but has been conditioned by other factors such as the level of media technology or the tasks or job position of each journalist.

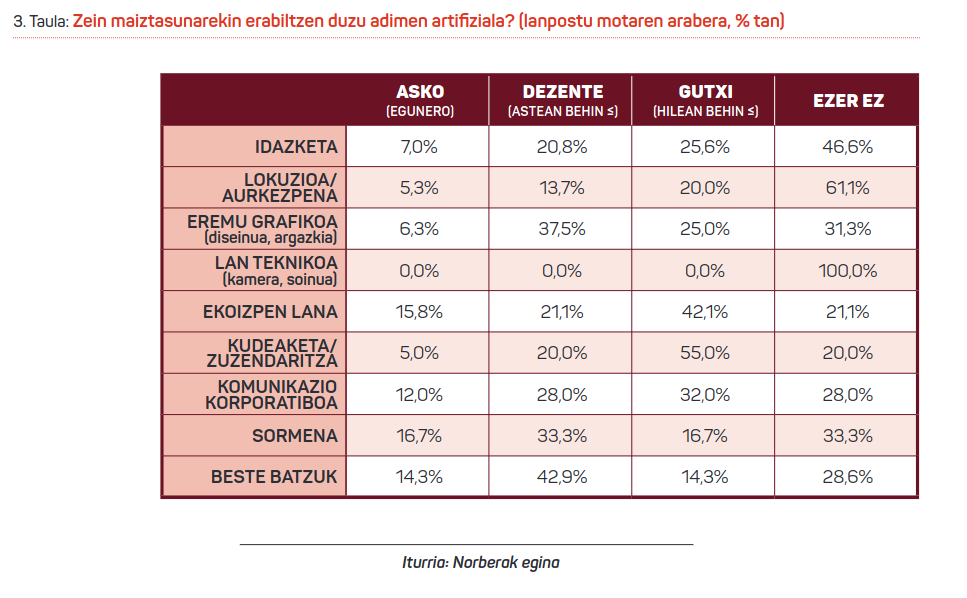

Thus, the data show that the frequency of the use of artificial intelligence varies significantly depending on the type of job, although the use of high frequency is relatively low in most areas (3. The table). In addition to the staff who carry out the technical work, the professionals who make the lowest use of this technology dedicate themselves to the tasks of speech or presentation (61.1%) or writing (46.6%). On the other hand, the number of those who make at least occasional use is much higher among the personnel dedicated to management positions (80%), production (78.9%) or corporate communication (72%).

This data by job position makes it possible to identify, at least temporarily, a trend in which media professionals (editors, presenters, etc.) directly related to the journalistic profession have so far been further removed from the use of artificial intelligence. ). On the other hand, other jobs working in the media, for example in technical areas, as well as in the areas of corporate communication and advertising, use this resource more often.

On the other hand, it is not surprising that people who hold a position of responsibility in the media make greater use of this technology. The disruptive nature of artificial intelligence and its potential impact on work are some of the factors that can weigh on this aspect and predict the trend towards the implementation and development of this technology in the media as prescribers.

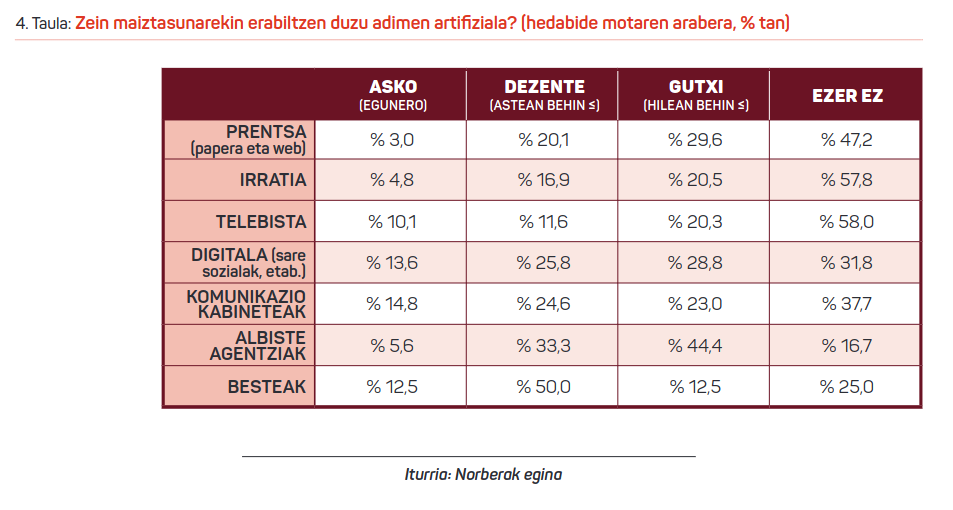

This same trend is confirmed in the case of the type of media in which professionals work. The professionals who work in traditional media and in companies most related to journalistic activity are the ones who use artificial intelligence the least. In the case of television, 58% of workers have never used artificial intelligence tools in their work. This figure is 57.8% in the radio and 47.2% in the press. On the other hand, employees who are further away from the contents of the gazette are already using this technology in a much more frequent way, and the number of those who make the usual use doubles in these cases.

Among the reasons that may explain these different adoption and acceptance rates among employees of communication companies may be, first of all, the distrust of journalists about the impact of this technology on the profession due to, for example, the lack of reliability of the data. Also, these workers may feel more distanced from the threat of being replaced by artificial intelligence, at least in the short term. On the contrary, in the case of people who work in more technical and related parts of the industrial production process, their use is greater. This technology has begun to contribute more to routine tasks that do not require supervision and are more economical than social in nature.

In any case, it will be necessary to monitor the advances in artificial intelligence in the areas most related to the profession of journalism, to see if the perception of the threat increases, and if journalists make greater use of these tools.

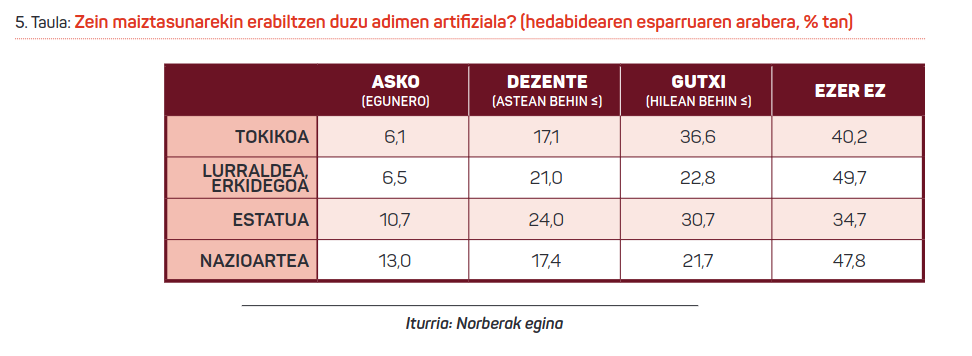

Finally, according to the data collected in the survey, the geographical scope of the media in which the professionals work also influences the acceptance and integration of technology (5. The table). In general, the use of high frequency (daily or weekly) is higher among media professionals who work in a broader field. Thus, professionals working in national media (34.7%) and international media (30.4%) recognize a higher use than in local media (23.2%) and regional/community media (27.5%).

In other words, the larger the extension área of the communication medium in which it is operated, the greater the possibility of using this technology. The reasons that may explain this trend may be varied: that these workers may be more likely to integrate this technology in their daily activities, that the companies they work for already have their own technological developments in this field, or that their daily work requires more use of these technologies.

The results also show that the application of artificial intelligence can be a new challenge for smaller media. Digital transformation can pose a risk of widening the digital divide for local media. Small media with limited economic and technological resources may face greater difficulties in competing with large digital platforms or media that have the opportunity to develop their own technological products. That’s why tackling the digital divide that artificial intelligence can strengthen will be vital to ensure the viability and sustainability of local media.

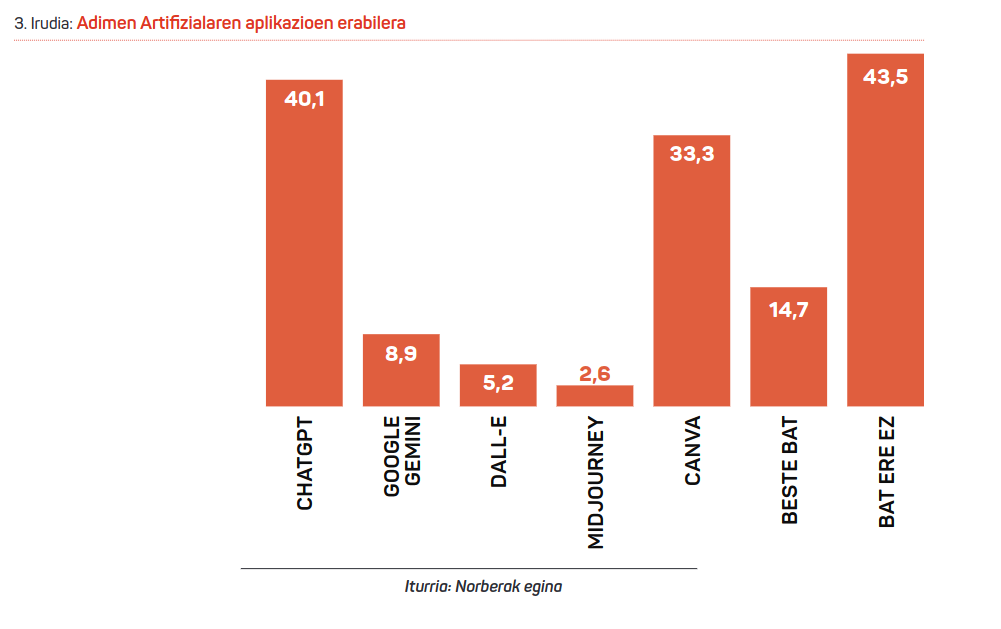

Finally, regarding the use of specific tools or applications of artificial intelligence, the results show a clear trend towards the use of ChatGPT (40.1) and Canva (33.3).

4. Conclusions

The data of this study confirm the forecasts advanced by previous studies on the local media conglomerate in the Spanish State (Cruz-Negreira, López García, Rodríguez-Vazquez, 2024). According to them, the local journalism lives in times of great changes. It needs to rethink and strengthen its survival strategies in a scenario where information deserts have proliferated, several nearby media outlets have disappeared and many information projects have difficulty maintaining the production and innovation rhythms imposed by the digital ecosystem. With the massive arrival of Artificial Intelligence (AI), many media outlets that have resisted the effects of adaptation are convinced that they need to review their strategies.

Digitalization and new technologies have transformed communication processes, but artificial intelligence represents a new revolution, automating the processing of data and improving the processes of creation and distribution of content. In general, the use of artificial intelligence by media workers in the Basque Country (CAPV) is still low and three out of four professionals do not use this technology, or do it very occasionally.

However, some differences in the use of artificial intelligence can be found by gender, experience, position and type of media. Thus, women have been more active users of this technology so far. Professional experience, on the other hand, does not significantly affect usage patterns.

Depending on the position, professionals in management and corporate communication positions use artificial intelligence more than those dedicated to presentation or writing. Thus, the more the job that is filled is related to journalism, the less artificial intelligence tends to be used. This can be influenced by the distrust of professionals about the potential impact of this technology on the profession (Peña-Fernández et al., 2023). In any case, the use of this technology by Basque media professionals will be essential to improve their individual skills and professional performance in a context of responsible and regulated use of artificial intelligence in the media.

As has been the case in the last three decades of the digital transformation of the media, the biases and dysfunctions that may arise from the use of this technology should be closely monitored. In addition to new opportunities to increase the added value of media professionals’ work, artificial intelligence can create new gaps, such as gender gaps, or gaps between platforms and big tech giants and local media.

Finally, strengthening the technological skills of journalists will be essential for the effective and responsible use of this technology. To this end, in addition to creating guidelines to ensure the ethical use and transparency of artificial intelligence in the media, specialized training programs will be necessary to develop the capabilities of this technological tool, but also to know the risks that its use may entail.

5. References

Beckett, C., Sanguinetti, P., & Palomo, B. (2023). New frontiers of the intelligent journalism. In Blurring Boundaries of Journalism in Digital Media: New Actors, Models and Practices (275-288). by Springer International Publishing.

Bernat, P. (2024). [The impact of generative AI on the work of journalists: tools and responses]. Journal of Journalism, 47.

Danzon-Chambaud, S., & Cornia, A. (2023). Changing or reinforcing the “rules of the game”: A field theory perspective on the impacts of automated journalism on media practitioners. Journal of Journalism Practice, 17(2), 174-188.

De Lima-Santos, M. F.; & Wilson, C. (2022). Artificial Intelligence in News Media: Current Perceptions and Future Outlook. Journalism and Media, 3(1), 13-26.

Díaz-Noci, J.; Larrañaga-Zubizarreta, J.; Larrondo Ureta, A.; & Meso-Aymedio, K. (2007). The impact of the Internet in the media of Basque communication. The UPV/EHU.

Basque College of Journalists (2024). To promote the ethical use of Artificial Intelligence in the media I. The Decalogue. https://bizkeliza.org/eu/noticia/ in media-intelligence -use-disability-boost-dekaloga-present-da/

Larrondo Ureta, A. (2017). Innovation and strategic adaptation in the convergence area: Response from information companies in the Basque Country. ZER, Journal of Communication Studies, 22(42), 97-117.

Larrondo Ureta, a.; & Peña-Fernández, S. (2024). [The formation of journalists in the era of artificial intelligence: aproximations from the epistemology of communication]. ThinkEPI Yearbook, 18(8), 1-5.

López-García, X.; & Pereira - Fariña, X. (From Coord.) (2010). The digital convergence: [Reconfiguration of communication media in Spain]. University of Santiago de Compostela.

Mayoral-Sánchez J.; Parratt-Fernández S.; & Mera-Fernández M. (2023). [Journalistic use of AI in Spanish communication media: current map and perspectives for an immediate future].Studies on the Periodic Message, 29(4), 821-832.

Mendique-Galdospin, T.; & Meso-Aymedio, K. (2016). Online marketing as a marketing strategy: the social media manager of companies. Mediatics, 15, 175-189.

Meso-Aymedio, K. (2003). [The formation of digital journalism]. Chasqui, 84, 4-10.

Meso-Aymedio, K.; By Díaz-Noci, J.; Salaverria, R.; Sádaba, R.; & Larrondo Ureta, A. (2005). [Presence and use of the Internet in Basque and Navarre diaries]. Euskonews & Media, 383.

Meso-Aymedio, K.; By Díaz-Noci, J.; Larrañaga-Zubizarreta, J.; Larrondo Ureta, A., (2011). Professional attitudes and employment situation of digital journalists in the Basque Country. The UPV/EHU.

Negreira-Rey, M.C. ; By López-García, X.; Rodríguez-Vázquez, A.I. (2024). The local periodsm reinvented strategies. Decálogo for Artificial Intelligence Time Challenges. Infonomy, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.3145/infonomy.24.008

Palomo-Torres, M.B. (2004). The online journalist: from the revolution to the evolution. From Social Communication.

Pérez-Dasilva, J.A. ; Mendique-Galdospin, T.; Meso-Aymedio, K.; Larrondo Ureta, a.; Ganzabal-Learreta, M.; Peña-Fernández, S.; Lazkano-Arrillaga, I. (2021). Digital profiles of journalists and dialogue with audiences in the Basque Country. The UPV/EHU.

Peña-Fernández, S. (2005). Training of journalists in the digital age. The mediatics. 11, 319-326.

Peña-Fernández, S., Meso-Aymedio, K., Larrondo Ureta, A., & Diaz-Noci, J. (2023). Without journalists, there is no journalism: the social dimension of generative artificial intelligence in the media. Information Professional, 32(2), e320227.

Sánchez-García, P.; & Campos-Domínguez, E. (2016). The training of journalists in new technologies before and after the EHEA: The Spanish case. Tripods, 38, 161-179.

Sánchez-Esparza, M.; & Palella-Stracuzzi, S. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in the Spanish Media: New Uses and Tools in the Production and Distribution of Content. According to In J. According to Al-Obaidi (Ed. ), About Changing Global Media Landscapes: Convergence, Fragmentation, and Polarization (283-302). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

Túñez-López, J.M. ; Fieiras-Ceide, C.; & Vaz-Álvarez, M. (2021). Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Journalism: transformations in the company, products, contents and professional profile. Communication & Society, 34(1), 177-193.

Ufarte-Ruiz, M. J.; In Calvo-Rubio, L. More about M.; & Murcia-Verdú, F. J. (2021). The ethical challenges of journalism in the era of artificial intelligence. Studies on the Periodic Message, 27(2), 673-684.